If you’ve ever split dovetails, tapped a stubborn joint into place, or assembled furniture without marring the surface, chances are you’ve relied on a trusty wood mallet. These seemingly simple tools are an essential part of any woodworker’s toolkit. Unlike metal hammers, wooden mallets distribute force evenly and gently, just enough to do the job without damaging your chisel handles, wooden pegs, or delicate surfaces.

In this article, we’ll walk through everything you need to know about wood mallets: how they’re made, which types to choose, when to use them, and even how to build your own. We’ll also review some of the best wood mallets available online, link to relevant DIY joinery techniques, and offer tips that come from real-world woodworking experience.

🪵 What Is a Wood Mallet?

A wood mallet is a striking tool made almost entirely of hardwood. It typically features:

- A large, flat head (usually rectangular or cylindrical)

- A long, comfortably gripped handle

- Balanced weight for controlled striking

Unlike metal hammers that can easily deform tools or crush workpieces, a wood mallet delivers a firm but forgiving impact. This is especially useful when working with chisels, joinery, mortise and tenon joints, or driving wooden pegs.

🖼️ Image Placement

Alt Text: Close-up of a wooden mallet resting on a walnut workbench.

Caption: A wood mallet allows for controlled force that won’t damage your tools or projects.

🧰 What Are Wood Mallets Used For?

Wood mallets are not just for looks. They’re engineered for specific jobs where you need force, but also finesse.

1. Chisel Work

When paired with a bevel-edged chisel set, a wood mallet lets you drive the blade precisely without cracking the handle or splitting wood fibers.

Affiliate Pick:

👉 Narex Bevel Edge Chisels with Mallet – These professional-grade Czech chisels come bundled with a matching wood mallet for under $100. Great starter set!

2. Joinery Assembly

Fitting dovetails, finger joints, or mortise-and-tenon work? Use a mallet to “persuade” parts together without deforming the edges.

3. Carving

Mallets are essential for woodcarving, especially when roughing out large forms. They deliver shock in a way that hand pressure alone can’t.

4. Adjusting Tools

Tapping the base of your hand plane or adjusting a workbench holdfast? A mallet does the job gently.

Explore hand plane adjustments ➝

🪚 How to Choose the Right Wood Mallet for Your Project

Choosing the right wood mallet isn’t just about grabbing the first one you see in the tool aisle. The best mallet for your needs depends on what kind of woodworking you do, your physical strength, and even your personal grip preference. Let’s break it down so you don’t waste money—or worse, damage your work or tools.

Weight matters. If you’re doing precision joinery, like dovetails or mortise and tenon joints, aim for a mallet in the 12 to 16 oz range. These allow for controlled tapping without overdriving your chisel. If you’re assembling large furniture or working on green wood, go heavier—18 to 24 oz mallets give you more force without having to swing harder.

Shape is also important. A traditional joiner’s mallet has a wide rectangular head with angled faces. These are perfect for distributing impact across the surface of a chisel handle. Carver’s mallets, on the other hand, are usually cylindrical and ideal for light taps and constant control. If you’re sculpting or doing relief carving, a round mallet that fits well in your palm will be far more comfortable.

Material counts too. Most good wood mallets are made from dense hardwoods like hard maple, beech, hickory, or ash. Avoid softwoods like pine or cedar—they’ll dent too easily. A laminated head can resist splitting better than solid blocks, though solid hardwood mallets tend to feel more balanced and last longer.

And finally, think about hand comfort. A well-shaped handle can make long sessions more comfortable. Look for a grip that’s rounded or contoured—not just a stick. Some woodworkers even wrap their mallet handles with leather or paracord for a softer grip.

Affiliate Pick:

🛠️ Wood Is Good 20 oz Mallet – Made from urethane with a hickory handle, this modern mallet has a dead-blow effect while still being gentle on chisels.

Choosing the right mallet isn’t just about what’s trendy or expensive—it’s about how the tool fits into your workflow. So test a few, feel the balance, and invest in the one that matches your tasks and your hand. If you’re doing joinery, a traditional mallet is a must. For carving, go round. And if you’re on the fence, having both isn’t a bad thing.

🔨 How to Make Your Own Wood Mallet (Beginner-Friendly DIY Plan)

Making a DIY wood mallet is one of those beginner projects that instantly makes you feel like a real woodworker. It’s simple, functional, and gives you a tool you’ll actually use for years. Best of all? You don’t need a workshop full of tools or rare wood to get started.

Start with choosing your wood. You’ll want two hardwood types: one for the head and one for the handle. Maple, oak, walnut, or beech are all great options for the mallet head. Hickory or ash is excellent for the handle, as they’re both strong and flexible.

Step 1: Cut your mallet head. A good size for beginners is around 6″ long, 3″ wide, and 2″ thick. You can adjust depending on your hand size or project type. Drill a ¾” square mortise through the center to accept the handle. You can use a drill press and chisels if you don’t have a mortising machine.

Step 2: Shape the handle. Cut a handle around 10–12″ long, and taper one end so it fits tightly into the mortise. It should wedge in about halfway through the head so it won’t fly off during use.

Step 3: Assemble it. Use a high-quality wood glue like Titebond III and clamp everything for at least 24 hours. For extra durability, you can wedge the handle through the top for a tight mechanical lock.

Step 4: Finish it. Round over the edges with a sander, then apply a coat or two of Tried & True Danish Oil or your favorite wood finish. It brings out the grain and protects your mallet from moisture.

This project not only teaches joinery and mortising, but you’ll walk away with a tool that’s 100% yours. If you’re into DIY toolmaking, you can even make matching chisels, handles, or a bench hook set to complete the kit.

🖼️ Image Placement

Alt Text: Homemade wood mallet with rounded handle and oiled finish resting on a pine workbench.

Caption: A DIY mallet is a rite of passage for any serious woodworker—and it’s easier than you think.

Let me know if you’d like one more H2 or if you want these placed directly into a canvas for further editing.

🪓 Types of Wood Mallets

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all mallet. Each design has a purpose. Here are the most common:

Traditional Joiner’s Mallet

- Large rectangular head

- Angled striking faces

- Heavyweight (up to 20 oz)

Best for woodworking joinery.

Recommended:

🛠️ Crown Hand Tools Rosewood Mallet – Solid rosewood with a comfortable handle and a striking weight for serious dovetailing.

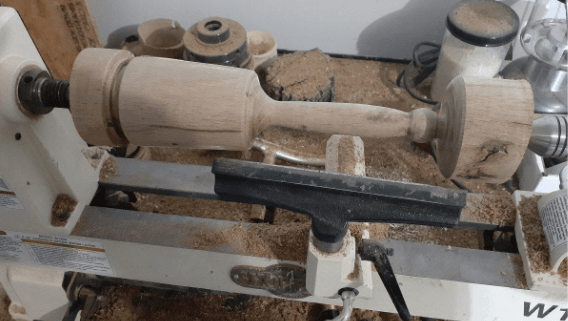

Carver’s Mallet

- Round or cylindrical head

- Often made from a single wood piece or turned on a lathe

Used in wood sculpture and relief carving.

Recommended:

🎨 Schaaf Tools Carving Mallet (18 oz) – Well-balanced and perfect for delicate carving work.

Dead Blow Wood Mallet

- Filled with sand or shot

- Minimizes rebound

- More common in composite materials, but wooden versions exist

Used for driving joints or knocking furniture frames square.

🌳 What Wood Are Mallets Made From?

The choice of wood dramatically affects how a mallet performs and holds up. You’ll often see mallets made from:

- Hard Maple – Extremely durable and resists splintering.

- Hickory – Shock-absorbing, often used in tool handles.

- Beech – Lightweight and economical.

- Lignum Vitae – Ultra-dense tropical hardwood, used in premium carving mallets.

DIY builders often use offcuts of hardwood flooring or repurposed butcher block.

🖼️ Image Placement

Alt Text: Comparison of maple, hickory, and walnut mallets on a workbench.

Caption: Dense hardwoods like maple and hickory hold up under repeated blows.

🛠️ How to Make a Wooden Mallet (Step-by-Step)

Want a personal touch in your shop? Making a mallet is a great beginner project.

Materials Needed:

- Hard maple, oak, or walnut block (for the head)

- Hickory or ash blank (for the handle)

- Wood glue

- Band saw or hand saw

- Chisels

- Clamps

Steps:

- Cut the Head

Rough out a 6” x 3” x 2” block. Drill or chisel a mortise for the handle. - Shape the Handle

Taper the end to fit snugly into the head. Dry-fit it before gluing. - Glue and Clamp

Apply wood glue to the mortise and insert the handle. Clamp for 24 hours. - Bevel the Edges

Bevel or round over the edges of the mallet to reduce chipping. - Finish

Sand and apply mineral oil or Tried & True Wood Finish.

More beginner woodworking projects ➝

🔍 What to Look for When Buying a Mallet

When shopping for a wood mallet online or in a store, consider these factors:

- Weight: 12–20 oz is ideal for joinery. Lighter for carving.

- Grip: A contoured handle with a matte finish helps reduce hand fatigue.

- Balance: A mallet should feel “neutral” in your hand, not too head-heavy.

- Durability: Laminated or turned solid wood holds up better over time.

🏆 Best Wood Mallets You Can Buy in 2025

Here are some top picks across different categories:

| Type | Best For | Product | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joiner’s Mallet | General woodworking | Crown Rosewood Mallet | Amazon |

| Carver’s Mallet | Fine carving | Schaaf Tools Mallet | Amazon |

| Heavy-Duty | Mortising | Wood Is Good Mallet (20 oz) | Amazon |

| Budget | Beginners | GreatNeck 46004 12 oz | Amazon |

🖼️ Image Placement

Alt Text: Grid of four different mallets: carver, joiner’s, dead blow, and DIY.

Caption: Your ideal mallet depends on your grip, your tasks, and your style.

❓ Wood Mallet vs. Rubber Mallet

Both mallets have their place—but they’re not interchangeable.

| Feature | Wood Mallet | Rubber Mallet |

|---|---|---|

| Best Use | Joinery, chiseling | Tapping metal, non-marring finishes |

| Rebound | Minimal | High |

| Precision | High | Low |

| Longevity | Durable (if hardwood) | Rubber can crack with age |

Need to move tile, install laminate, or set pavers? Go rubber. Need to chisel dovetails? Wood is king.

Read: Best Tools for Laying Tile on Plywood

🧽 How to Maintain Your Mallet

Even the toughest mallet wears down over time. Here’s how to keep yours in top shape:

- Oil it monthly with mineral or linseed oil to avoid drying or cracking.

- Reshape faces with a belt sander if they become mushroomed or chipped.

- Store in a dry shop, not in a humid shed or freezing garage.

- Check joints for wiggle or looseness, especially in glued handles.

🎯 Final Thoughts: Do You Need a Wood Mallet?

Absolutely. If you do any sort of joinery, carving, or general woodworking, a wood mallet gives you a level of precision and care no metal tool can offer.

Whether you go with a beautiful rosewood model or make your own from scrap hardwood, owning a wood mallet shows you’re serious about craft, not just construction.

🧾 Bonus: Mallet Safety Tips

- Never use a wooden mallet on metal tools unless they’re designed for it (like chisels with wood handles).

- Don’t strike with the edge of the mallet head—use full contact with the face.

- Wear eye protection, especially when working with aged or cracked wood.