At the most basic level, a house consists of walls and a roof, mounted on a foundation. Granted, there are a lot of other things that go into most homes, like plumbing and electrical; but I’m talking about the basic structure of the house itself. We can have all the wiring and piping in the world, but not have a house if we don’t have walls and a roof. But on the other hand, it can still be a house, albeit not one built to code, if the walls and roof don’t have plumbing and electrical installed.

Not all walls are considered equal though. While it’s obvious that there’s a difference between exterior and interior walls, there’s another important distinction between them. That is the difference between load-bearing walls and partition walls. Anyone who is going to do any remodeling that includes adding, removing or moving walls had better know the difference between the two.

Load-bearing walls include all of those which are holding something up. This includes all the exterior perimeter walls of the home, but it usually includes some of the interior walls as well. Specifically, if you divide a home in half, along its longer dimension, there is probably a wall running down the center. This wall may not be exactly on center and it will probably have doorways going through it, but it will be there, holding up the ceiling joists. It can most easily be identified in the attic, by looking for where the ceiling joists overlap each other. That will be sitting on this load-bearing wall.

Newer homes, which use trusses for the roof, rather than rafters, may not need as much support for the ceiling joists as homes with rafters do. That’s how they can build these homes with huge living areas that aren’t partitioned. But once again, looking at it from up in the attic may very well show that there are trusses which end at some point, over a wall, while other trusses pick up from that point, usually at a right angle, continuing to support another section of the roof.

The other walls inside a home, which do not support the rafter or truss are considered to be partition walls. We can move or remove any of these walls, without it affecting the overall structure of the house. On the other hand, any time a load-bearing wall is moved, something needs to be done to support whatever it is holding up.

When it comes to doing remodeling projects around the house, most people will try to avoid messing with load-bearing walls. But what about the partition walls? Since they don’t support any weight, adding new ones or taking out old ones really is no big deal. It’s the type of thing that can be a good weekend project.

Not all partition walls are even the same. There are a few situations where a cement partition wall might be used. Then there are temporary partition walls, something like those used to make cubicles in offices. But for most homeowners, the term “partition walls” refers to 2”x 4” framed walls.

Keep in mind that there’s usually more to moving a wall than just moving the wall itself. It’s not unusual to find plumbing, electrical and ductwork inside the hollow cavity in the walls. In addition to that, flooring has to be considered, as the floor covering is usually added in after the walls were built. So, if the home has carpeting on one side of the wall and tile on the other side, the floor covering will have to be cut back on one side of the new wall location and the other side will need to have new floor covering installed.

Framing a Partition Wall

Adding or moving a partition wall in a home can cost anywhere from $500 to $1,500 depending on whether or not there are any doors in the wall that have to be purchased, what sorts of wall treatment might be used and of course, what sorts of floor covering need to be added or replaced. But the actual work for most of this is something that the average homeowner who is handy with tools can handle themselves.

Partition walls are framed from 2”x 4” studs, with longer 2”x 4”s used for the sole and top plates. If possible, it is best to use 2”x 4”s for the plates which are long enough to span the entire length of the wall, without splicing them. However, if plates that long are not available, then splices in the double top plate should be staggered 48” from each other. Splices in the sole plate should have a short piece of 2”x 4” scabbed to the top side of them, to hold the pieces together while raising the wall. Once the wall is attached in place, the attachment to the floor will hold the sections of the sole plate together.

Before building the wall, determine where it will go and clear the area. That may mean removing floor and wall covering, as well as removing popcorn texture from the ceiling. If there is any furniture or other items in the way of where the wall will go or in the work area in general, they will need to be removed for the duration of the project.

The top of the wall will need something more than drywall to attach to. If the new partition wall is perpendicular to the ceiling joists, this isn’t a problem, as it can be nailed through to those joists. But if the new partition wall is running parallel to the joists, then it might be necessary to add blocking between the joists, above the ceiling, for the top plate to attach to.

It is easier to lay out and assemble a framed wall with it laying down on the floor and then tip it upright, attaching it in place, than to build it upright. The major difference is that when building it laying down, the studs can be nailed to the plates by nailing straight through the plates into the ends of the studs. If the wall is built upright, all of the studs need to be toe nailed, both at the top and bottom.

While I show a double top plate in the drawing below, this is not absolutely necessary for a partition wall, if there will not be any new drywall attached to the ceiling. The main purpose of that double plate is to ensure that there will be something for the top edge of the drywall on the walls to be attached to, after the ceiling drywall is installed. However, if a single top plate is used, it is possible that 8’ long 2”x 4”s will need to be purchased and cut to length for studs, rather than the standard 92 5/8” long.

In any case, the ceiling height should be measured before material is purchased and the wall framework is assembled. Typical 92 5/8” studs will create an 8’ tall wall, when used with a double top plate and a single sole plate. But if there is already drywall in place, then the ceiling height will probably be ½” less than 8”. In the case of a nominal 9’ ceiling, the studs are usually 104 5/8”. But the drywall will actually make the ceiling height ½” less in this case as well.

Note that in the drawing below, the sole plate runs the full length of the wall, even though it will have to be cut out, once the wall is raised. Leaving that section in the wall, while building and raising it, ensures that the two sections of the wall are in alignment with each other, once the wall is raised and fastened in place. If that section is not left there, there is a good chance that the walls will be out of alignment with each other and the door will not close properly.

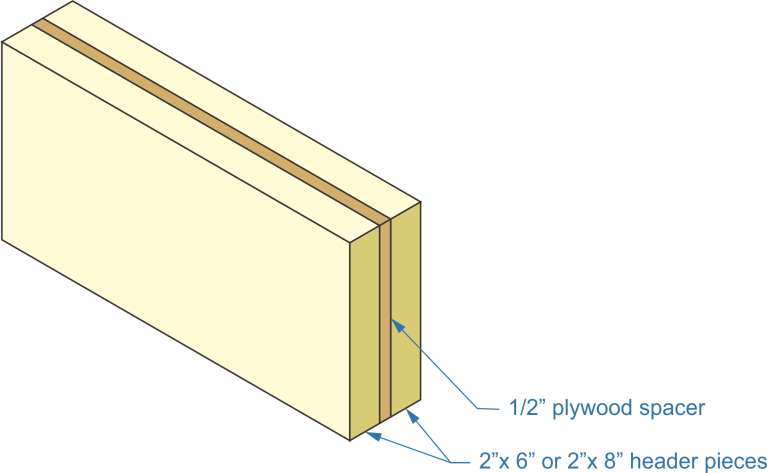

Cut and lay out all the pieces on the floor, before starting assembly. studs are spaced every 16” on center. The header, above the door, is made of two pieces of 2”x 6” for a single door or two pieces of 2”x 8” for a double door. The pieces need to sit upright when the wall is raised, so that they will do the best possible job of resisting flexion. So to make the two pieces the same thickness as the 2”x 4” wall framing, nail them together using 8d box nails, with a ½” plywood spacer in-between them.

The double stud at the right end of the wall is only necessary if the wall will be joined with another, making an inside corner. In such a case, the wall that is erected first will have the end stud covered up by the end stud on the second wall, leaving the end of the drywall without anything to be attached to. Adding blocks of scrap 2”x 4” and then a second stud ensures that the second stud is far enough away from the end of the wall, so that when the second wall is raised, there will still be something for the drywall to attach to.

To nail the pieces of the wall frame together, nail through the top and bottom plates and into the ends of the studs, using two 16d box nails for each stud. It is better to use coated nails, as the glue coating helps prevent pullout of the nails, which may be an issue if the home settles. In the case of using a double top plate, nail the first plate to the studs, and then nail the second plate to the first.

The header is attached by nailing through the king studs into ends of the header, using three 16d box nails per piece for 2”x 6” header pieces and four 16d box nails per piece for 2”x 8” headers. It is best to have the trim studs nailed to the king studs, before installing the header; so as to ensure that there is a snug fit between the pieces. The cripple studs will have to be toe nailed to the top of the header, although they can be nailed to the top plate the same way that the common studs are.

With the entire wall framed, it can be tipped up and set into place. If it is a snug fit, it is better to put the top in place first, then use a heavy hammer to pound on the side of the sole plate, shoving it into place. Once the wall is properly aligned, nail it to every ceiling joist and to the floor between every pair of studs. In the case where the wall is being installed over a cement floor, powder actuated fasteners can be used to attach the sole plate to the floor.

Now that the Structure is In

With the wall structure in place, the next step is to install any wiring needed for switch plates and wall outlets. According to the US National Electric Code, wall outlets need to be installed every six feet, as measured at the floor line. This will probably require damaging the adjacent wall somewhat, so as to gain access to string Romex from the nearest electrical outlet on an adjacent wall to the new wall.

If the home is a one-story home, it is possible to avoid damaging the adjacent wall by running the electrical line down from the attic. The majority of the home’s electrical wiring is probably already running through the attic, so it may be quite easy to find the existing wire bringing power to that room’s outlets. If it can be found, then it can be cut and the new wire attached with wire nuts. Be sure to mount an electrical box in the attic for this, making the connection within the box.

In the case where the wiring cannot be found, the new outlet(s) can still be attached to the same line by running a wire up from one of the existing electrical outlets, inside the wall, up to the attic and from there over to the new section of wall, where it can go back down. Doing this requires figuring out where the outlet is, from the attic side and then drilling a hole down through the top plate of the old wall, in a place that is directly over an existing outlet box. Then use an electrical snake to run the new wire down to the existing box, attaching it to the existing outlet (they’re designed to have more than one set of wires attached) or to the wires, connecting it with wire nuts.

This should leave the bulk of the Romex still up in the attic. Another hole has to be drilled through the top plate of the new wall, just above the new outlet location. The end of the wire can then be fed down through that hole for connection.

Back down at the wall, mount a single-gang electrical box to one of the studs, six feet from the nearest existing outlet. Typically these are mounted 12” above the floor, but it might be a good idea to check the height of existing outlets, so that it can be mounted the same. Run the end of the wire into this box, then cut off the excess, leaving about a foot of wire hanging out. If necessary, holes through the studs to run more Romex to the next outlet location.

It probably won’t be necessary to add plumbing and HVAC ducting to your partition wall, unless you’re moving a wall. But if they are needed, such as in moving a wall for a bathroom remodel in which the bathroom is going to end up bigger, those changes need to be made, before the drywall can be installed on the wall.

Installing Drywall and Trim

Drywall typically comes in ½” thickness, although other thicknesses are available. Nevertheless, ½” thick is the correct thickness to use for covering an interior wall. Sheets are 4’ x 8’ and should be hung horizontally, with the upper sheet (butting up against the ceiling) installed first. Start from one corner and work out from there, making sure that the sheets are butted tightly together. Drywall can either be nail or screwed (1 ¼” long) to walls, with the fasteners installed every 8”.

The second (lower) course of drywall is then installed, with the joints staggered four feet from those on the upper course. That will help reduce the visibility of the seam, once the wall is finished.

It may be necessary to cut the bottom of this second course of drywall off, so as to fit. When installed, the drywall should have a ½” gap at the bottom to allow for expansion and shifting of the house. Running the drywall all the way down to the floor increases the chances of the walls cracking.

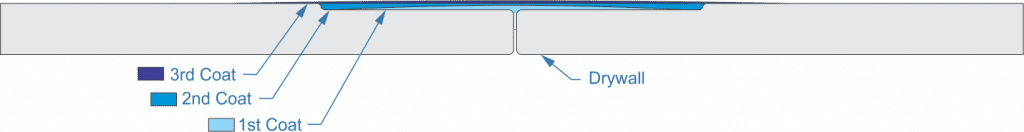

With the drywall installed, it’s time to tape and finish it, using drywall mud and tape. There are various types of drywall mud that can be used, but for a small project like this, it’s best to use all-purpose drywall mud, rather than bothering with taping mud and then finishing mud. Fiberglass tape is easier to work with than paper tape, although it is more expensive.

All the joints between sheets of drywall, including between the new drywall and pre-existing drywall need to be taped and finished. The long edges of the drywall are inset slightly, making it easier to tape and finish these edges. This is important, as any horizontal seam would be more obvious than a vertical one is. With paper tape, a layer of mud is applied, and then the tape, as the mud is needed to hold the tape in place. Excess mud is squeezed out by running back over the tape with a drywall knife. With fiberglass tape, the tape is applied first, as it is sticky, then the mud is applied over it.

There will normally be a total of three coats of drywall mud applied to new walls, although some cases may require a fourth coat. Make each coat as thin as possible, allowing them to dry and sanding them between coats to remove any rough spots. With each coat, the size of drywall knife used is larger, making for a wider layer, feathering the mud out for a finished seam that is roughly 14” wide; so:

- The first coat is applied with an 8” drywall knife and the nails or screw are covered with a 6” putty knife

- The second coat is applied with a 10” drywall knife and any visible nails or screws are covered with a 8” drywall knife

- The third coat is applied with a 12” drywall knife

When finished, it should be possible to run one’s hand over the wall, without feeling any perceptible bumps, ridges or rises at the joints or fasteners.

Spray orange peel texture onto the wall, covering it entirely. If the ceiling had popcorn texture on it and some of it had to be removed, touch up the ceiling before doing the wall. Texture guns can be rented at any tool rental. Once the texture has dried, the wall can be painted. Then install the baseboard, door casing and any other trim desired to finish out the wall.