When you remodel a kitchen, laundry room, or garage, one of the biggest hurdles is figuring out how to hang wall cabinets. Normally, you’d screw directly into wall studs. But what happens if your studs don’t line up—or worse, you have no studs in the right place? That’s when you face the challenge of figuring out how to install wall cabinets without studs safely and securely.

This guide will cover:

- Why studs matter and what happens when they aren’t available

- Anchoring options that work without studs

- Tools and hardware you’ll need

- Step-by-step installation methods

- Safety considerations and weight limits

- Real-world tips from DIY projects

By the end, you’ll have the confidence to mount wall cabinets securely—even if your wall framing doesn’t cooperate.

Understanding the Risks of Installing Cabinets Without Studs

Before you try to install wall cabinets without studs, it’s important to understand the risks involved and why proper anchors matter. A wall cabinet is more than just a box on the wall—it’s a piece of furniture that will be loaded with dishes, pantry items, or tools, sometimes weighing hundreds of pounds in total. Without studs to support that weight, you’re asking drywall or plaster alone to carry the load, and that usually fails.

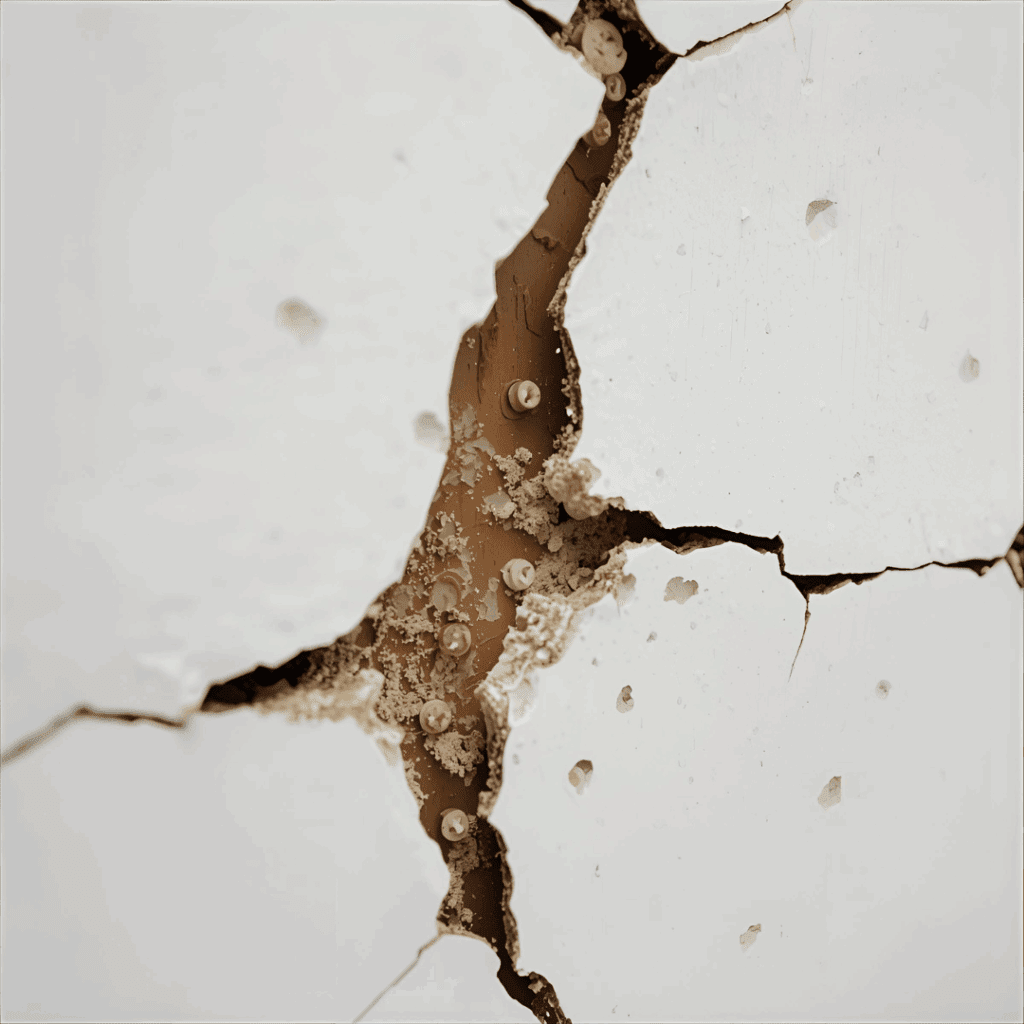

One of the biggest dangers is that the cabinet may appear secure at first, but gradually loosen over time. Drywall can start to crumble around screws, causing cabinets to sag, lean forward, or even pull completely out of the wall. This isn’t just inconvenient—it’s a serious safety hazard if heavy items come crashing down. It can also damage your walls, flooring, and anything stored inside the cabinet.

Another risk lies in improper anchor selection. Many homeowners make the mistake of grabbing inexpensive plastic drywall anchors, thinking they’ll do the trick. While these might hold a picture frame or a towel rack, they are nowhere near strong enough for cabinets. That’s why heavy-duty hardware like toggle bolts, molly bolts, or a French cleat system is essential if studs aren’t available.

Finally, keep in mind that even the strongest anchors have weight limits. If you underestimate how much your cabinets will hold, you may exceed the safe load without realizing it. Being proactive—by using multiple anchors, spreading the load, and reinforcing cabinets with adhesives or rails—will give you peace of mind that your setup will last for years.

Why Studs Are Important for Wall Cabinets

Wall studs are vertical framing members—usually 2×4 or 2×6 lumber—spaced every 16 or 24 inches on center. They act as the backbone of your walls and provide structural strength.

When you mount a cabinet directly into studs, you:

- Distribute the cabinet’s weight safely. By anchoring into studs, the load spreads across solid lumber instead of relying on weak drywall.

- Prevent drywall from cracking or tearing. Stud support keeps the wall surface intact, avoiding unsightly damage that happens when anchors pull loose.

- Ensure cabinets stay level over time. Proper stud attachment prevents sagging, which can throw doors out of alignment and make cabinets look uneven.

Without studs, you’re relying on drywall, plaster, or hollow wall space, which cannot support heavy loads on its own. Without studs, you’ll need to install wall cabinets without studs using specialized anchors designed to carry a heavy load.

Can You Really Hang Cabinets Without Studs?

Yes—but only if you use the right anchors and techniques. Drywall alone will fail under cabinet weight. The secret is using heavy-duty wall anchors or creating an alternative support system.

Cabinet weight varies:

- Small bathroom cabinets: 20–40 lbs empty

- Kitchen wall cabinets: 40–80 lbs empty

- Loaded with dishes/pantry items: 100–300+ lbs

Because of this, your hardware choice matters more than ever.

Best Hardware for Hanging Cabinets Without Studs

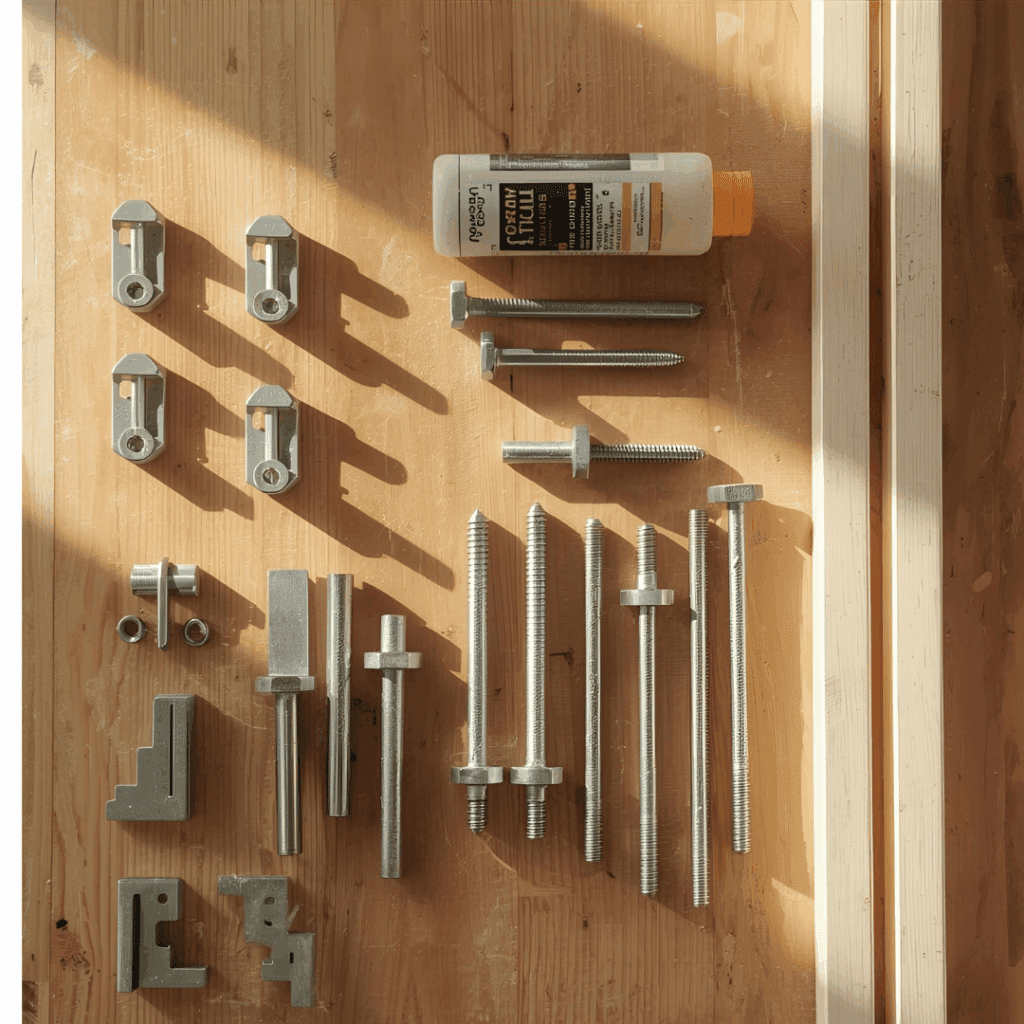

1. Toggle Bolts

Toggle bolts expand behind the wall, creating a strong grip. They’re one of the most reliable fasteners when studs aren’t available.

- Supports 50–100 lbs per anchor.

- Great for hollow walls and plaster.

- Requires drilling a larger hole.

2. Molly Bolts

Molly bolts work similarly to toggle bolts but lock in place more permanently. Once installed, they won’t spin or loosen.

- Supports medium loads (25–50 lbs each).

- Works well for medium-sized cabinets.

- Better than plastic anchors.

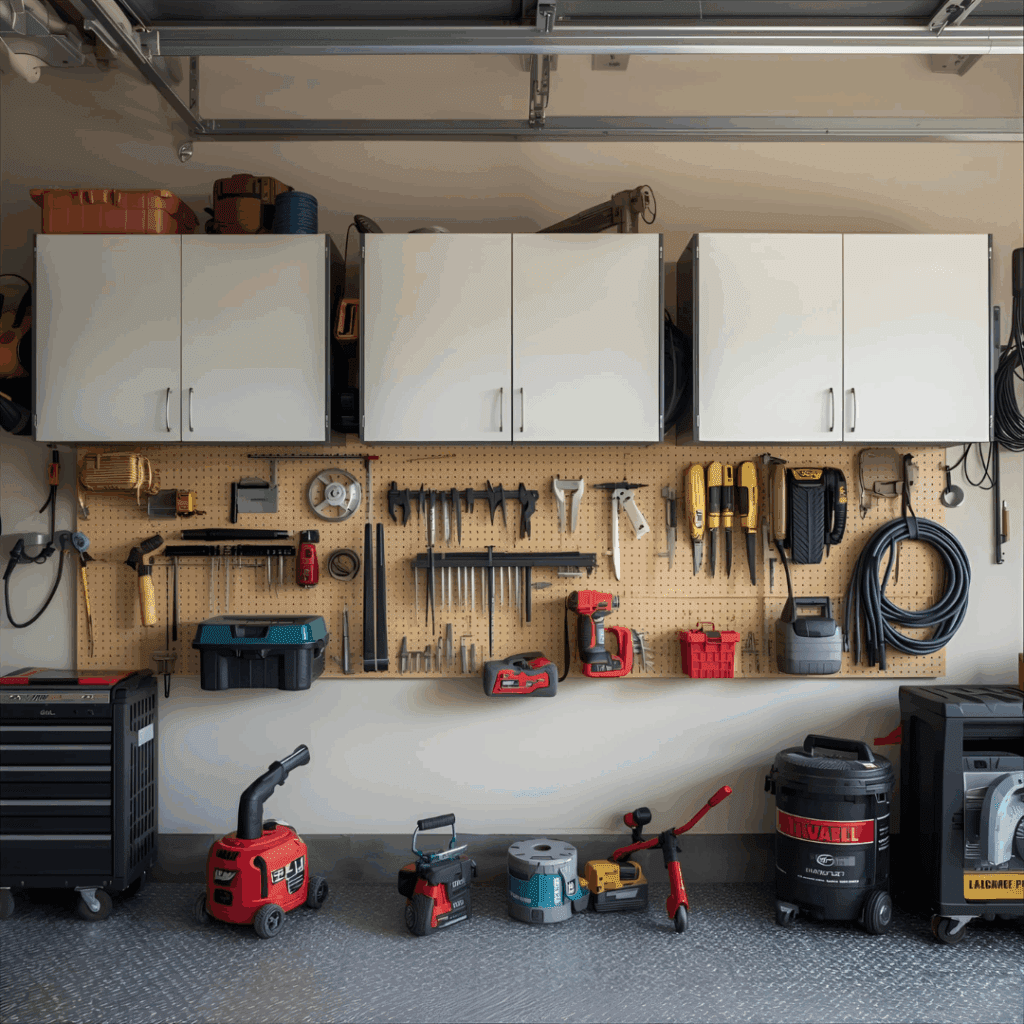

3. Cabinet Hanging Rails (French Cleats)

A French cleat system distributes cabinet weight evenly across the wall. Instead of relying on one or two bolts, the weight is spread along a metal rail.

- Professional-grade solution.

- Handles very heavy cabinets.

- Requires precise installation.

4. Self-Drilling Drywall Anchors (Not Recommended Alone)

Plastic or metal self-drilling anchors are common, but they aren’t strong enough for cabinets on their own. Use them only as supplemental support.

5. Construction Adhesive (Supplemental Only)

Some pros use adhesive + anchors for extra strength. Adhesive spreads the load across a wider surface. But never rely on glue alone.

Tools You’ll Need

- Stud finder (to confirm stud absence)

- Level and chalk line

- Power drill + drill bits

- Screwdriver or impact driver

- Tape measure

- Safety glasses and gloves

Step-by-Step: How to Install Wall Cabinets Without Studs

Step 1: Measure and Plan

Mark the cabinet layout on the wall.

Use a level to create a straight line for the cabinet bottom.

Double-check for plumbing/electrical behind walls.

Expansion: Take time to mark both the bottom and top of the cabinet line to avoid crooked placement. Pre-drill small guide holes for reference so you know exactly where each fastener will go before lifting heavy cabinets.

Step 2: Locate Any Available Studs

Even if studs don’t align perfectly, use at least one if possible. Then supplement with anchors.

Expansion: If you find a stud close to the cabinet edge, anchor one screw directly into it for added stability. Combining at least one stud connection with heavy-duty anchors greatly reduces the risk of cabinets pulling loose over time.

Step 3: Pre-Install Cabinet Hanging Rail

If using a rail system, install it first. Drill holes at intervals and insert toggle bolts or molly bolts. Tighten firmly.

Expansion: Ensure the rail is level before tightening, as the entire cabinet will rely on this alignment. Use a temporary support board or ledger under the rail to keep weight off the fasteners while you work.

Step 4: Drill Anchor Holes

Toggle bolts: Drill holes slightly larger than the folded toggle. Insert and tighten until snug.

Molly bolts: Drill pilot hole. Insert the bolt and tap with a hammer until flush. Tighten to expand wings.

Expansion: Always check the weight rating of each anchor and use more than the minimum recommended. Spacing anchors evenly across the cabinet back spreads the load and prevents stress cracks in drywall.

Step 5: Mount Cabinet

With a helper, lift the cabinet into place.

Secure through the cabinet’s mounting rail into wall anchors.

Re-check the level before final tightening.

Expansion: Use clamps or temporary ledger boards to hold the cabinet in place while driving screws, reducing the strain on your arms. Tighten each anchor gradually instead of all at once to maintain even pressure and keep the cabinet square.

Step 6: Add Extra Support

Apply construction adhesive to the back edges.

Anchor adjoining cabinets together for shared strength.

Expansion: Run a bead of adhesive along the top and sides for added contact, especially if your wall surface is uneven. Once multiple cabinets are installed, screw them together through the side panels so the entire row acts as one solid unit.

Safety Tips and Weight Limits

Whenever you install wall cabinets without studs, overbuilding with extra anchors is the safest approach

- Always overbuild. Use more anchors than the minimum. This ensures your wall cabinets without studs stay secure even if one anchor loosens over time.

- Distribute load. Spread anchors across the top and bottom rails. Even weight prevents the drywall from cracking under concentrated pressure points.

- Avoid particleboard walls. They lack strength. Cabinets mounted into weak substrates can tear loose quickly and pose a safety risk.

- Don’t overload cabinets. Store heavy items in base cabinets instead. Reserve wall cabinets for lighter dishes, food items, or supplies to extend their lifespan.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Underestimating the weight of dishes/pantry. A fully loaded cabinet weighs far more than you think and can exceed safe anchor limits.

- Using plastic anchors alone. These anchors often fail under cabinet weight and can pull out without warning.

- Forgetting to level cabinets. Even a slight tilt will become noticeable once doors and shelves are installed.

- Installing into damp or crumbling drywall. Weak surfaces compromise anchor grip and lead to early failure.

- Not checking for hidden pipes/wires. Drilling blindly can cause expensive and dangerous damage.

Real-World Solutions: Case Examples

- Garage Storage: French cleats held 200 lbs of tools. The homeowner noted that even after years of use, the cabinets stayed level and secure, showing how reliable cleats are for heavy-duty storage.

- Small Apartment Kitchen: Toggle bolts + adhesive secured cabinets for 10+ years. This method allowed the tenant to maximize storage in a tight space without damaging studs or needing major renovations.

- Laundry Room: Molly bolts worked fine for lightweight shelves, but failed under detergent jugs—reinforced with a rail system. Once the rail was added, the setup easily handled the extra weight and gave the wall a much cleaner, professional finish.

Alternative Solutions

- Build a plywood backer board attached across multiple studs, then mount cabinets onto it. This method creates a continuous structural surface, letting you secure cabinets anywhere along the wall without worrying about stud alignment.

- Use freestanding pantry cabinets instead of wall-mounted ones. These are easier to install, often provide more storage, and eliminate the risk of anchors pulling loose from drywall.

- Install floor-to-ceiling cabinet walls for weight support. This approach combines upper and lower cabinets into one solid unit, transferring the load directly to the floor for maximum stability.

👉 Recommended link: Best Plywood for Cabinets.

Conclusion: Secure Cabinets Even Without Studs

Mounting wall cabinets without studs takes planning, the right hardware, and a focus on safety. Toggle bolts, molly bolts, or cabinet rails can all provide lasting strength. When in doubt, overbuild—and remember that the integrity of your installation comes down to the quality of your anchors.

For most DIYers, I recommend:

- French cleats for maximum safety.

- Toggle bolts as the best all-around anchor.

- Adhesive + anchors for added security.

By following these steps, you’ll learn how to install wall cabinets without studs in a way that’s strong, safe, and built to last.