Shadow boxes are a specialized form of frame, most commonly used for framing three dimensional objects so that they can be hung on the wall. Whether that’s the ribbons and medals won during military service, a signed team jersey from one’s favorite athlete, a flag presented at a military funeral or dollhouse or house miniatures that you love and have been collected over the years for home alone, they can all be attractively displayed in beautiful shadow boxes for home alone.

When using shadow boxes to show off miniature collectibles, the shadow box is usually broken up into different sections, providing cubby hole for each item. These are rarely covered over with glazing of any sort, but if small children are around, it would be a good idea to do so. Adding the glazing is not all that difficult.

Shadow boxes can also be used to mount artwork. Sometimes, this is done with the artwork in the back of a glass-covered shadow box, with some related object set in front of the picture. Other times a painting on canvas might be mounted in a shadow box without glass, using the shadow box as a frame. Regardless of what’s being mounted in the box, shadow boxes provide a distinct manner of framing items to be hung on the wall, in a way that tends to make items stand out more than normal framing.

Unfortunately, commercially manufactured shadow boxes are considerably more expensive items than frames. That’s a bit odd, especially considering that the design is usually rather simple compared to other frames that use elaborate moldings. But this just gives us that much more reason to make our own. Besides, the availability of different sizes is somewhat limited.

Before making any shadow box, there are a few things that need to be decided:

- Is the shadow box going to be glazed? If so, with what sort of glazing?

- Will the shadow box be divided into sections?

- How will the shadow box be finished? (sometimes they are painted black on the inside)

- How big and how deep does the shadow box need to be, to accommodate what’s going to be on display inside it

While some shadow boxes exist which have wider frames; that is rather rare. When it does happen, the face of the frame is normally a separate piece of glass, attached to create the face of the shadow box display. In some cases, this face is made as a separate, hinged piece, allowing access to the contents inside of the shadow box.

Making a Non-Glazed Shadow Box

It is easier to make a non-glazed shadow box than a glazed one, so we’ll start there. The first step in making any shadow box is determining the size of the box. In order to do that and be sure it is correct, it’s a good idea to mount whatever is going to go in the shadow box to the backboard. This means cutting the backboard and painting it to start the project. Keep in mind that there will be some space taken up by the frame, so leave at least ¾” of backboard all the way around.

The frame itself can be made out of any 1” thick boards (which are actually ¾” thick). It’s better to use hardwood for a build of this than softwood, as it will cut cleaner and be less likely to dent. Start by ripping the wood to measure the depth of the shadow box, taking into consideration the space needed for the backing board and the overall depth desired.

Then cut the individual pieces slightly long and cut to create a rabbet to accommodate the backboard into one edge. This rabbet should be at least ¼” wide and about ¼” deeper than the thickness of the backboard.

With the rabbet cut, miter cut the pieces so that they will fit around the backboard, leaving 1/16” of space all the way around. Then attach the pieces together. When this step is done commercially, it’s often done by a combination process of gluing and nailing, with the nail holes then being filled. But it’s better to do it without the nailing, if possible.

Okay, so how do we do that?

One of the easiest ways to assemble any miter joint is by using painter’s tape to hold the parts together. The tape is placed sticky side up on the workbench and the pieces making up the joint aligned on it. This is critical, as the pieces must butt up exactly with each other and also be in a straight line to each other. Use a long straight edge to check that.

- Apply glue to the mitered surfaces and then bend the joint, bringing the surfaces together.

- Repeat for the opposite pair; then join the two sets together.

- Adding a band clamp around the entire frame will help hold it together until the glue dries.

- Once dry, the frame can be finished and the back installed.

Another option is to nail all the corner. If this is being done without using the painter’s tape or band clamp just mentioned, then I highly recommend using a corner clamp to hold the pieces together while nailing. The act of nailing tends to make pieces slide against each other anyway and the presence of glue will act as a lubricant, helping them to slide even more. Without being clamped while nailing, the chances of getting a clean mitered corner are extremely slim.

Once the frame of the shadow box is assembled, the backboard can be set into the rabbet that was cut into the back of the frame earlier. There are several ways of attaching this in place, including gluing it and nailing through the sides. I prefer to use glazing points, pushed into the frame from the inside, to hold the backboard in place.

Adding Splines to the Shadow Box’s corner

One way of making the shadow box stronger, without having to use nails through the sides, is to choose to install splines in the corners. This not only adds a considerable amount of strength, but if the splines are made out of a contrasting type of wood, can add an attractive detail to the shadow box’s appearance.

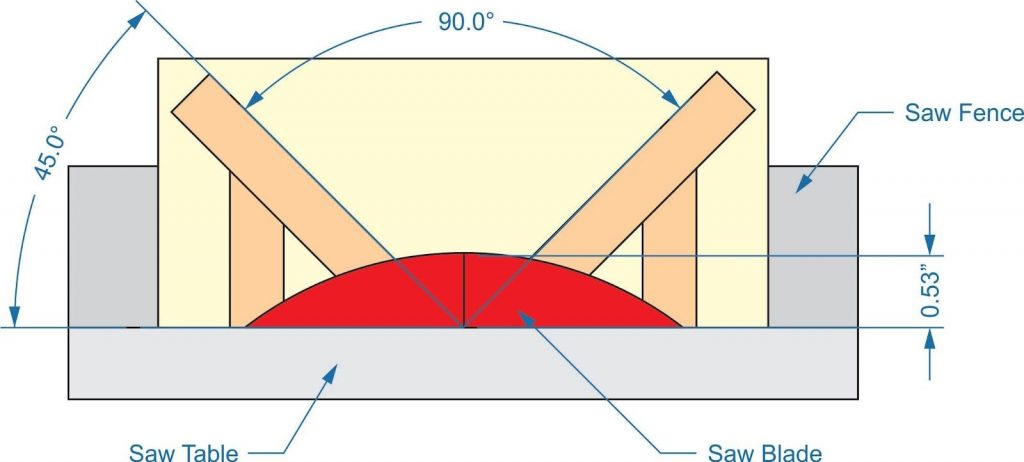

In order to add splines to the shadow box, it’s first going to be necessary to cut slots for the splines to be inserted into. This is most easily done on the table saw, using a special jig to hold the frame in position. In the diagram below, the jig is shown as a cutaway, so that the blade is visible; but it needs to extend past the blade, acting as a zero clearance insert, to help prevent splintering of the shadow box. The frame is placed in the jig, with one corner down and the jig is run against the table saw’s fence to align it for cutting.

Splining jig

For shadow boxes made of ¾” thick material, the blade should be set to 0.53” (17/32”) high. Typically, more than one spline is used per corner, but the splines shouldn’t be any closer to each other than one inch.

Carbide tipped table saw blades are typically 1/8” thick. So it will be necessary to cut some wood strips 1/8” thick on the table saw or on a band saw. The table saw is probably best for this, as it will provide a smoother surface. Then cut the strips into pieces that are at least 1-1/8” long, for the individual splines.

Glue the splines into the slots by first putting glue into the slots, either with an acid brush or a glue bottle with a needle on it. Then insert the splines fully, checking to be sure that there is material sticking out both sides of the cut, so that there won’t be any gaps in the shadow box’s surface when the splines are cut. Allow the glue to dry fully, and then cut the splines flush with the shadow box’s surface with a flush-cut saw. Sand the surface smooth.

Making a Wider Shadow Box Frame

If a wider shadow box frame is desired, the common way to accomplish it is to add another frame, made out of wider material, on top of the existing one. The key to making this work is to make sure that the inner dimension is the same or just a shade smaller than the shadow box itself. If it is a shade smaller, the dividing line won’t be so obvious; but if the frame is larger, the dividing line will show.

This second frame can either be made of 1”x 2” boards, architectural molding or framing molding. It is best to assemble it right to the existing shadow box, rather than to make it separately and then attach it.

Either way, it will be necessary to nail the top frame to the shadow box, so the trick is going to be hiding the nails so that they aren’t visible in the finished project. To do that, sink the nails below flush with a nail set, then fill the hole above the nail head. Allow the putty to dry and sand it smooth before finishing.

Adding Dividers to the Shadow Box

The open-faced shadow box is easily converted for use with photos and small collectibles by adding photos and dividers. These items and photos are generally made as an insert and then installed into the shadow box. In most cases, the photos and dividers are made the same depth as the shadow box, so that they sit flush with the surface.

Dividers are often made out of ¼” thick material and are built following a geometric pattern, so that all of the pieces of wood go all the way across to create the shadow box. This is considerably easier to do, as it is much easier to connect the pieces together and measure them then to install them in the box.

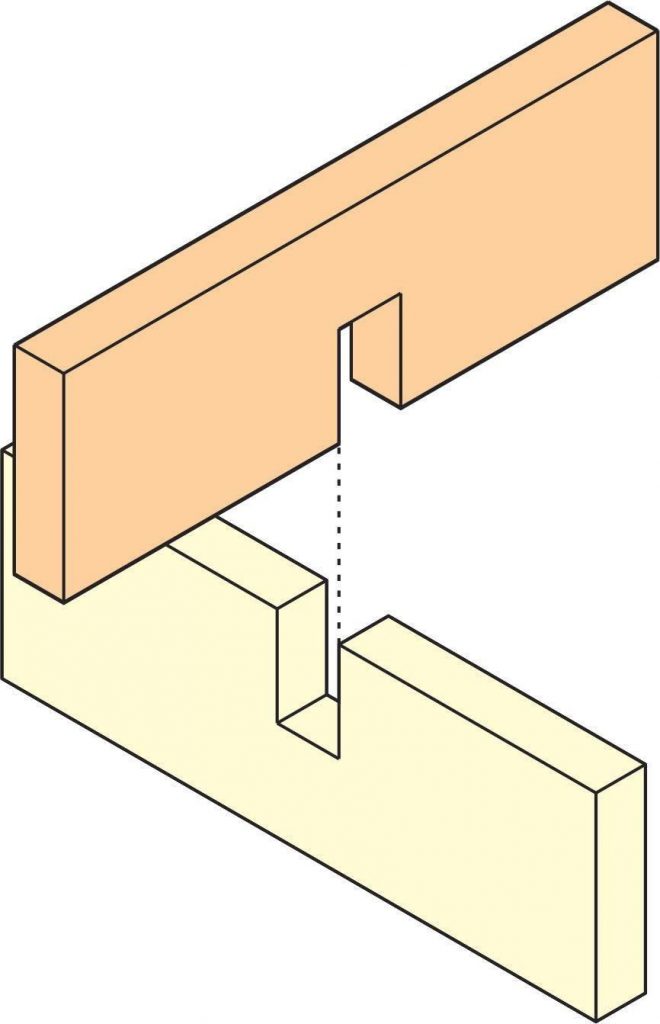

Joining them together is best accomplished by notching the individual pieces where they cross each other, so that they can be interlocked, as shown in the diagram below.

Interlocking joint

This is very easy to cut on the table saw, using a sled. Hold the pieces against the side of the sled, so that they are standing on edge, with the blade set to the cut depth. It will probably take more than one pass to get a perfect cut the thickness of the board being used. It doesn’t matter if the cut is a touch too long, as the extra won’t be visible once the two pieces are put together.

When assembling the dividers use wood glue inside to secure and fill all the notches that have been cut. Wood glue can also be used to attach the dividers into the shadow box, especially nice if the grid fits snugly. However, it is usually best to nail through the back panel, into the edge of the divider and secure the grid with either short brad nails or pin nails.

The big problem with doing this is that it is extremely easy to miss the dividers when nailing, leaving a nail sticking through the backplane. To help prevent this, draw the dividers on the back of the backplane, providing guides to go by and help ensure the nails are in the right place.

Making a Glazed Shadow Box

It is considerably harder to make a glazed shadow box, than it is to make an unglazed one. Nevertheless, it is still something that can be carried out by the average woodwork, in the company, at the house, company, home, family or home workshop. The challenge comes in because the glazing needs to be installed in the box. This means cutting the pieces of the sides to allow room for the glazing, and then filling the cut out area back in.

To start with, mount the object to be framed close to the backboard, so as to ensure that the shadow box will be large enough. Then determine the depth of the shadow box, keeping in mind that there will need to be space at the back of the shadow box for the backboard, plus about 3/8” of space at the front of the shadow box for the glazing to hang from. That will provide enough depth for the glazing itself to hang and room for the lipl over the glazing to hold and secure it in place.

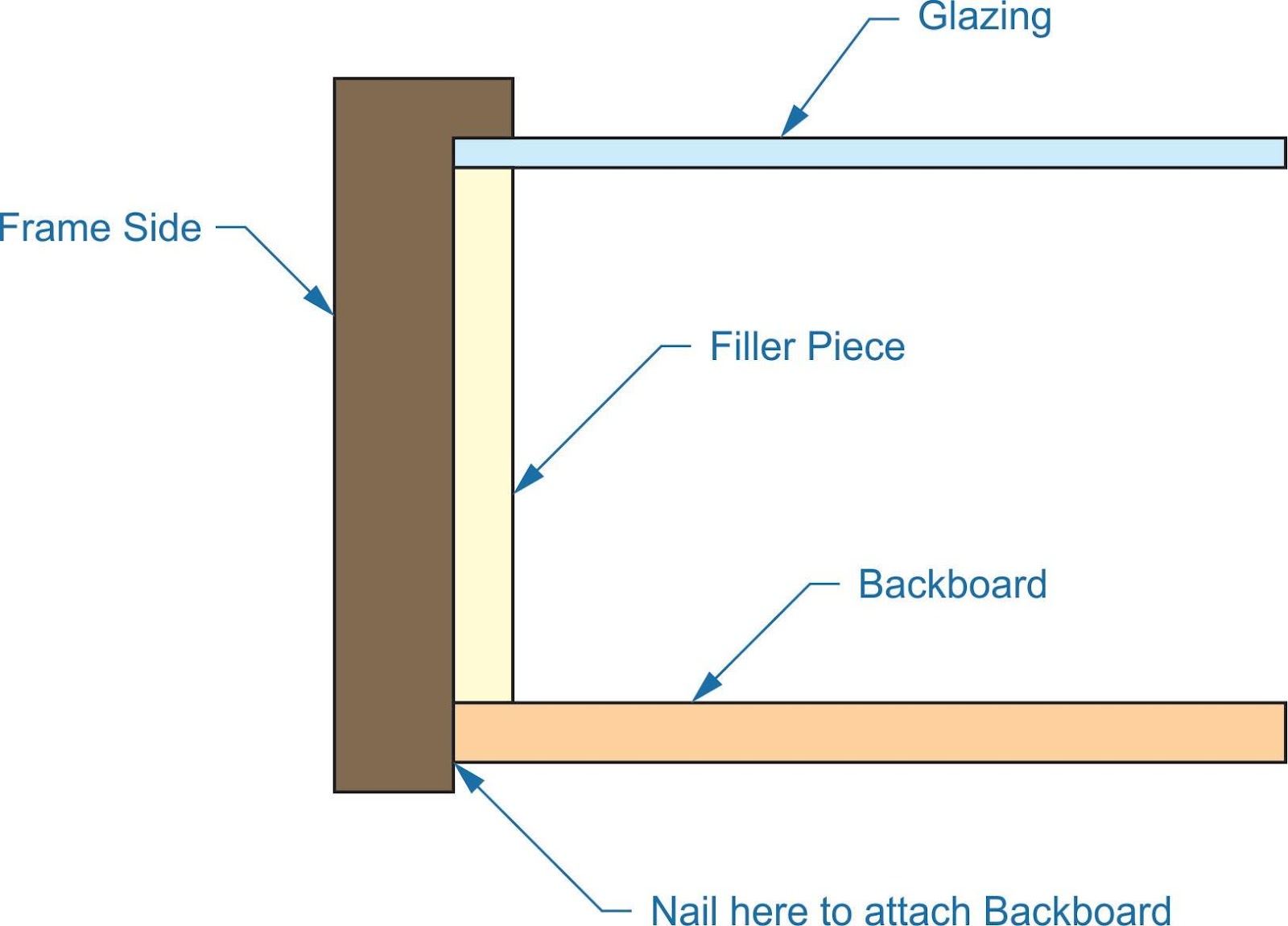

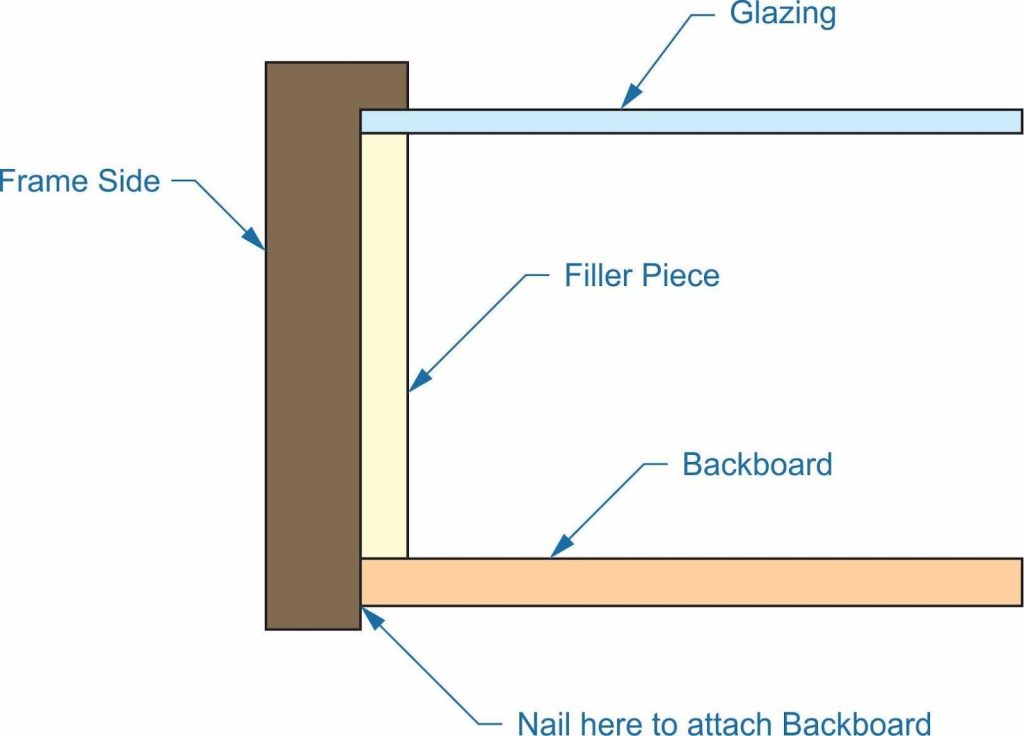

Glazed shadow box

The tricky part of this shadow box is making the pieces for the frame sides. As we can see in the diagram above, the frame sides need to have a large rabbet cut into them, larger than is reasonably possible with either a rabbeting plane or a table saw.

The solution to this problem is to cut the majority of the material out with a straight bit in a router table, leaving a lip at the back, just like there is on the front. Don’t worry that the surface isn’t smooth, as it will be covered with the filler piece. Then, when everything else is cut out, cut off the lip at what will be the back side of the frame, on the table saw, with the piece standing vertically up against the fence.

It will probably be easier to do projects of this with four smaller pieces, rather than doing the whole board and then cutting it to size. Even so, it’s a good idea to cut half the pieces for the sides too long, ignoring the miters, and then cutting the miters after the side pieces have been hollowed out.

Since any mistakes or splintering on the router table will most likely happen at the ends, cutting half the parts long allows those mistakes to be cut off when the corner are mitered.

Once the pieces are hollowed out and mitered, they can be connected together in the same way mentioned above for the unglazed shadow box, either with or without using a spline.

With the shadow box frame assembled, it should be finished before anything else is done. Then, once it has been finished, the frame can be flipped face side down on the workbench and the glazing set in place.

The filler pieces shown in the diagram above are what will be holding the glazing in place. This is ¼” thick plywood and it needs to be ripped on the table saw to fit snugly between the glazing and the backboard, leaving room behind the backboard for the fasteners that will hold it in place.

To save on having to cut all four of these pieces accurately, work around the shadow box, cutting each piece just a touch shy and installing it. No miter is required, as the next piece will cover up any gap. The only piece that needs to be cut extremely accurately is the last one to be installed, as it has to butt up tightly with the pieces on both sides. These pieces need to be finished before they are installed.

These pieces can either be installed with double-sided masking tape or with wood glue. If they are to be glued in place, cover the strips with pieces of 1”x 4” for clamping, as they are thin and tack on. Adding the 1”x 4”s will allow the clamping force of whatever clamps are used to be spread out, holding a wider area.

Once the display filler pieces are installed and the adhesive has had time to dry, the display backing board, with whatever is to be shown off in the display shadow box mounted to it, can be installed. As mentioned earlier, this can be glued in, nail in place or held in place with glazing points.