Quality joinery is the defining mark of the experienced woodworker. We start learning joinery with the first project we make, putting two pieces of wood together, and spend the rest of our woodworking career improving upon that. There are so many different types of joints to make, many of which require some actual practice to develop the skill to do them well, that we can spend years trying to become even marginally proficient at them all.

Joinery also means learning how to work with wood glue, although that shouldn’t take us as long. But what do we mean when we use the term “wood glue?” There are several different wood glues that we might use, and while the average woodworker has a favorite that they reach for regularly, there are always projects that require other types of glues.

The most common wood glue that most of us use is PVA glue, which stands for polyvinyl acetate. Many standard glues fall into this category, including white school glue. The original Titebond and Titebond II wood glues are PVA glues. However, the main difference between yellow PVA glues and white glue, such as Elmer’s glue, is that they have lower water content. That’s important to woodworkers, as high water content can cause swelling and warping of wood and affect the glue’s gap-filling capability. While yellow wood glue isn’t considered to be gap-filling in the same way that epoxy is, it is better at it than white wood glue.

Types of Wood Glues

As I already mentioned, there are several different wood glues in addition to PVA glue. The most common ones are:

- Titebond III – The main difference between this and the other Titebond wood glues is that they are waterproof. Titebond II is water-repellant but not waterproof.

- Gorilla Glue – This is a polyurethane glue intended to be a general-purpose glue rather than just a wood glue. It adheres to a broader range of substrates than Titebond III will. As with all polyurethane glues, it is moisture-activated, making it ideal for use with wood with high moisture content. However, it will foam due to the moisture, making it come out of the joint. That provides excellent gap-filling capability, but it can be challenging to clean up.

- Titebond Extend – A slower-setting version of the original Titebond wood glue. This is used in applications requiring complex clamp-ups, as it offers a longer assembly time.

- Epoxy – Although not customarily considered wood glues, epoxies are excellent for woodworking, especially for gappy joinery. The high solids content of epoxy makes it an excellent choice where gaps must be filled without losing strength. All epoxies are high tensile strength. They are also helpful as a finish or when potting wood might be required, such as when making a “river” tabletop or for woodturning. Epoxy can also be used as a high-build, clear finish.

- Cyanoacrylate Adhesives – Commonly referred to as “superglue,” although that is a specific brand of CA glue. This category of adhesives is excellent for repairs of all types. They are highly fast-setting, and the gel versions provide excellent gap-filling. Cyanoacrylate adhesives are also a hard finish, especially for string instruments.

- Dry Hide Glue – This type of glue harkens back to the old days of woodworking, where cabinetmakers kept a glue pot to keep their hide glue hot and pliable. It is made from animal hide and is the only wood glue designed to heat and disassemble the parts. Although not used daily, it is still available and is excellent for veneering work.

- Contact Cement – A high-tack glue used predominantly for the application of veneer. Contact cement is so suitable for veneering that once it tacks and the glue makes contact with itself (on another surface), it bonds instantly. Extreme care must be used when working with contact cement, but there is no risk of the glued veneer coming up once pressure is removed.

- Construction Adhesive – Normally only used in construction work, construction adhesive is a heavy-bodied adhesive sold in caulking tubes. It is an excellent gap-filling adhesive, which is why it is used. However, it doesn’t bond with the wood surfaces like other wood glues, soaking into the wood’s pores. So, while it might hold parts together almost instantly, it does not form as strong a bond as wood glues.

Choosing the right glue for the application is an essential part of woodworking. Common yellow PVA “wood glue” will work for most projects. However, knowing the other types of wood glue and when to use them is essential to any woodworker’s mental toolbox.

Clamping Wood Joints

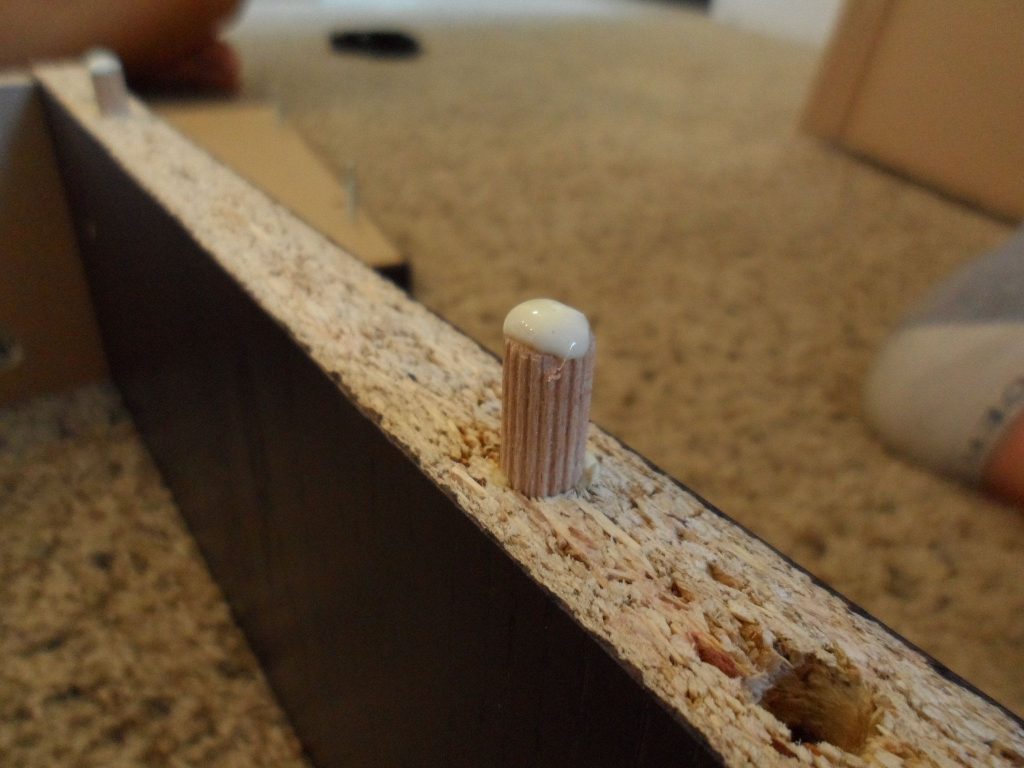

Proper clamping is an essential part of any glue-up, perhaps even more important than the type of glue selected. Clamping does three critical things for the woodworker: it puts the wood pieces in the proper position concerning each other; it eliminates gaps between the pieces so that the glue doesn’t have to span those gaps; and it ensures that the pieces remain in alignment with each other while the glue dries or sets.

A proper clamp requires sufficient pressure to ensure that gaps in the joint are fully closed. Different types of clamps provide various levels of clamping force, so it is crucial to ensure that the proper clamps for the project are selected.

Clamp can be simple or complex, depending on the project being made. By and large, it is better to do several simple clamp-ups than perform one complex one. Even so, there are times when a complex clamp-up is required due to the project’s complexity.

To do multiple clamp-ups rather than a more complex one, it is necessary to have an excellent understanding of how the project fits together. In many cases, there is a particular order in which parts need to be clamped together into assemblies. If that order is broken, we can find ourselves in a position where we need to glue parts that can no longer be put together because of other joints that have been glued.

Understanding the working time of any specific wood glue is vital. When the working time is exceeded, the joint created with that glue weakens. Dry clamp of a project is an excellent means of determining the clamping order, verifying that the joints fit together correctly, and ensuring that sufficient clamps are available to complete the clamp-up. Sometimes, complex clamp-ups have to be broken down into several more straightforward stages simply because there aren’t enough clamps available to complete the more complex clamp-up.

Glue Dry Time

Once the wood is clamped, it should be untouched until the glue is fully set. This doesn’t just mean surface drying of the glue but all the way through. As most of the glues mentioned above air dry, complete glue drying can take several hours. By and large, the only exceptions to that are the cyanoacrylate adhesives family and the epoxy family. Epoxy is unique amongst all glues used in woodworking in that it is cured by a chemical reaction rather than drying by evaporation.

For air-drying wood glues, such as the more common PVA adhesives, an essential dry time of 30 minutes is typical. But that assumes the parts will not be under load or stress. For complete drying, so that the joints can be put under load or stress, it is necessary to give the joint 24 hours. That means the project should be left clamped for 24 hours.

Allowing a full 24 hours of clamp time before any secondary operations is critical to avoiding problems with the project coming apart during those operations. We can include cutting, drilling, planning, and sanding in this list of secondary operations. While some adhesives can fully dry quicker than that, this is true of almost any type of wood glue, regardless of the kind. If the project is unclamped or the work is attempted during the dry time, there is a high probability of the project coming apart, even if only partially so. This creates a much more serious problem than just regaling the pieces back together, as the resulting joint will not be as strong as the original one would have been.

Please note that sanding glue, which isn’t dry, grinds particles of the glue into open pores in the wood. This can have the additional effect of closing off those pores, affecting the appearance of finishing operations. Both staining and varnishing require open grain in the wood, and anything that closes off the grain is likely to cause discoloration in the affected area.