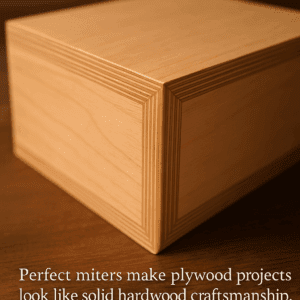

Plywood can be difficult to join together, especially when you are looking to make an invisible joint, where no hardware is exposed. The typical method of attaching pieces of a plywood cabinet casing together at the corners is with nails or screws, leaving a finishing mess.

But it’s very easy to split the plywood that way, laminating it. Even if the plywood doesn’t’ split it can bulge out, not putting enough side pressure on those fasteners to hold well. You’re also left with holes from the hardware exposed and needing filling. While acceptable for rough work, this sort of joint is not acceptable for cabinetry or furniture.

Gluing cut edges of plywood isn’t very effective, as the cut edges combine end grain with the side grain in the wood, leaving little space for a good glue joint. For a glue joint to hold, the side grain needs to be glued, not the end grain. Glue pulls out from end grain much too easily, making a weak joint. The various types of plywood corner joints which can be routed into the edges of boards help with this, but only to a point.

This leaves a lot of people looking at the kind of specialty hardware that is used for assembling it yourself furniture. But while those types of hardware have become popular in the furniture industry, they are expensive for use in your own projects. Lesser cost hardware, like using corner brackets on the inside, are unsightly and don’t hold very well.

However, with a biscuit joiner, clean, unobtrusive joints can be made in plywood, with no visible hardware and clean edges coming together. Whether joined together at 0 degrees, 45 degrees or 90 degrees, all joints are clean and tight, as well as being strong. It’s almost as if the biscuit joiner was invented specifically for use in joining plywood together.

Biscuit Joining

Biscuit joining uses a small compressed wood disk as the joining medium. The biscuit joiner tool cuts slots in both pieces, which this disk is glued into. As opposed to using dowels, which have to be very precisely located, the slots that a biscuit joiner make have enough play in them to allow for minor misalignment, making them much easier to use. Because of the cut, the biscuit is totally hidden.

The general idea behind biscuit joining is that it provides a solid side grain to side grain surface for gluing, providing for glue adhesion. The biscuits themselves are made of compressed wood and are actually thinner than the slot that the tool cuts. This is done with the intention that the moisture in the glue will cause the biscuit to swell, filling the slot and making a tight connection. This method can be considered to produce a floating mortise and tenon joint.

The key to successful biscuit joinery is a proper clamping job. While the tool provides an accurate cut, the built-in slop in the joint will leave you with an uneven surface, if you don’t clamp it correctly, making sure to add cauls to ensure that the surface of the boards are flush with each other.

Even though the fit of the biscuits into the slot that the biscuit joiner tool makes has a considerable amount of slop, the cut the tool makes is extremely accurate. The tool is designed for this, with gauges built into them to ensure the position of the blade, in relation to the surface of the wood. Nevertheless, your best setup comes from using the wood you are going to join as a gauge for setting the fence position. That way, there is no error from miscalculation or misreading the gauge.

Using the Biscuit Joiner Tool

To adjust the fence on the biscuit joiner, set one of the pieces you are going to join flat on the workbench. The bench must be clean and clear of sawdust and chips. Check that the workpiece is laying flat and then set the biscuit joiner’s fence to 90 degrees. Place it on the workbench so that the fence overlaps the edge of the workpiece. Once in place, the adjustment knob can be used to set the fence’s position. The fence adjustment is usually a small knob. This is intentional, so that you don’t have much leverage. You want to raise the fence enough that it is not in contact with the workpiece; then lower the fence until it makes good contact. You will be able to tell when that happens, as the knob will immediately become very hard to turn. Stop and tighten the locking screws.

The cut you are making with the tool is a plunge cut into the edge of the board or sheet of plywood. To ensure accuracy, the tool’s fence must make good contact with both the surface and edge of the board being cut. Make the cut in one smooth stroke, without going back to clean it up. A second plunge cut will invariably make a sloppy cut into the side of the board, enlarging it and reducing the contact area.

Biscuit size

The only other adjustment on the biscuit joiner is for the size of biscuit used. These range in size from 0 to 20, in increments of 5. In most cases, you’re best off using the largest size biscuit that will work with your project. Setting the size of the biscuit on the tool adjusts the depth of cut for the blade. This adjustment ensures that it cuts half the biscuit’s width into each piece.

With the biscuit joiner properly set and the workpiece on the bench, the bench top acts in conjunction with the fence, to ensure correct alignment. Before cutting, mark both boards to be cut, so that you can place the cuts opposite each other. A slight offset isn’t a problem, as the slots the biscuit joiner will create are slightly longer than necessary, allowing you some longitudinal adjustment of the workpieces. With both pieces cut, glue is applied, the biscuit inserted and the workpieces clamped together to dry.

Pros and Cons of Biscuit Joining

When biscuit joiners first came out in the 1990s, they were the tool that every woodworker had to own. But they’ve become much less popular since then. This is because of a maturing in the woodworking community’s understanding of this tool. The early infatuation has been replaced with healthy skepticism. While there are still woodworkers who swear by the biscuit joiner, there are many more who prefer other methods of joining wood together.

Pros

- The biscuit joiner is considerably easier to work with than cutting mortise and tenon joints, doweling or using pocket screws. This makes it a favorite for newbie woodworkers.

- Biscuit joining is quick, which makes it good for mass production.

Cons

- Biscuit joining doesn’t add any appreciable strength to a joint, like doweling or other mechanical fasteners do.

- Because of the slop in the slot, it is easy to misalign a joint, leaving you with surfaces that need to be planed smooth.

Alternatives to Consider

While biscuit joining is popular, you may want to consider using other, more traditional, means of joining plywood or boards together, especially as your skills as a woodworker increase. A good collection of joinery methods that one is competent in making is an important part of any woodworker’s tool kit.

- Dowels – The use of dowels is probably the nearest analog to biscuit joining and quite probably where the original idea came from. Dowel jigs are notoriously difficult to work with, which explains why many woodworkers don’t like using them. However, they add considerably more strength to a joint, than a biscuit will.

- Mortise & Tenon – Cutting a mortise and tenon allows the wood itself to form the joint. This is ideal for frames, where one board is butting up to another at 90 degrees; what might otherwise be a butt joint. However, it is not useful for laminating boards together to make a tabletop. Cutting a mortise & tenon requires considerable skill.

- Lap Joint – When it is necessary to have two pieces come together to make that but joint, but you don’t want to go through the trouble of making a mortise & tenon, an easier option is to make a lap joint. This is where half of the thickness of each board is removed at the joint and they are overlapped and glued together. Nails or dowels can be added, through the thickness, but are not absolutely necessary.

- Dado Joint – A dado joint is when a dado or slot is cut into one board and the other is set into this slot. This is useful with both boards and plywood, for things like shelves and cabinetry. The weakness of a dado joint is that there is very little side grain for gluing. However, the glue going into the end grain on either side of the dado can’t pull out, as it normally can from end grain, because it is wedged in place by the other board. Screws or nails must be used in conjunction with the dado.

- Pocket Drilling – When making a cabinet face frame, where a butt joint is required, one of the more popular methods of joining is with pocket screws. A special jig is required for this, allowing you to drill the pocket at a shallow angle. Screws can then go from that shallow pocket into the side grain of the other piece, making a very strong joint.