Through the years, I’ve worked with several table saws, from my dad’s venerable Craftsman to a Delta Unisaw to the portable table saw I used in construction. I learned through all this that the fence is an essential part of any quality table saw.

The fence included some essential buts. Most will say that the blade and the blade drive are the most important parts.

Bubit there, I agree they are important; I don’t think they are more inconsistent finish quality woodworking fence. If there’s a little wobble in the blade to designed or aligned drive, it will mar the consistent finish accuracy of the cut. But if the precise alignment of the fence is off, the amount will be crooked. That’s a bar problem to deal with.

Different Table Saw Fence

But not all fences are created equal. If there’s one thing I’ve seen through all the table saws and fences I’ve used, it’s that there are a lot of poorly made table saw fences out there. If you’ve got a table saw with one of these fences, the standard fences, the bad ones, or the walls, it will affect the quality and precision of every cut you make.

You can do two things besides installing a table saw fence; systems go with it. The first is to buy another table saw. The second is to build yourself another table saw fence.

While some reasonably complex tabletop fence designs are out there, you can make one quickly with the best table saw, providing excellent service. But first, there are a few key features and things that you need to keep in mind when designing and building any table saw fence:

- Perpendicularity – The key thing any fence has to do is maintain perpendicularity with the saw’s table. Another way of looking at this is that it has to remain parallel to the saw blade. Poorly designed table saw fences don’t have enough crossbar for the “T” portion, causing it to wobble.

- Rigidity – Any table saw fence will only work if it can maintain rigidity. It can’t flex under the pressure of material wedged between it and the saw blade, especially if the cut starts crooked.

- Security – When you clamp the fence, it has to stay there, no matter what. Just as with rigidity, there are times when the material between the fence and the sawblade will push against the side of the fence, trying to move it. That can’t be allowed to happen.

- Ease of Use – which is hard to move, and clamp will not be used. This is why commercially manufactured fences have an over-the-center clamp. That’s fine if you’re making it out of metal, but a wood over-the-center clamp will only last so long. Therefore, I’ve chosen another design.

For the fences in this design, I’m using a combination of fences made of wood and aluminum extrusions rear support rail. The fence itself, the part that guides the wood, is made of wood, but the “T” head and the rail are made of aluminum. That allows me to take advantage of the strengths of the two materials, applying them where they will do best.

Making the Fence Rail

I chose a 12 gauge piece of 1-1/2″ square “C” channel for the fence rail. This is the same sort of channel that you might see used for the rail on a horizontal sliding door in a factory or a gate.

Usually, these are made of steel rather than aluminum, but I’ve used aluminum for weight. If you can’t find this material in aluminum, you can just as easily make it out of roll-formed steel.

Typically, a fence rail is the width of most table saws, but I’ve extended it six inches beyond the table’s edges on both sides. This ensures that my fence rails will still maintain perpendicularity, even when at the extreme tips and advantages of the table saw itself.

Extensions

If you were planning on building extensions onto your table saw table, I’d do that before building the fence rails or make your table saw fence just long enough to accommodate those while extending past the edges of the table saw itself.

The saw’s table should already have holes drilled and tapped into the front edge of the vega table from the original fence rail.

You should be able to use these same holes if you remove and install the existing fence rail. You may need to drill some additional fixes if mounting holes are insufficient. As the table top is probably made of cast aluminum, this should not be a problem.

Be sure to mount the table and install the brackets on the guide rail so that it is slightly below the table’s surface to ensure that it will not hold the table and fence off the table’s surface.

Also, ensure that it is perfectly level or parallel to the table’s surface so that the weight of the table and fence doesn’t ride up and down the rear rail vertically as it moves across the table.

Building The Fence

I’ve chosen to use MDF (medium-density fiberboard) for the fence. Another perfect fence option would be applewood plywood if you can find it.

The thin plies of the applewood are extremely stable and perfect for this sort of project. That stability is why I chose MDF, which is easier for me to get.

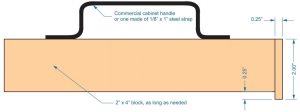

The fence comprises four ¾” thick strips of MDF, all 3″ wide. Because I am working with a stock fence that is not all that reliable (the one I’m trying to replace), rather than count on the precision and durability of the fence’s clamping system for perpendicularity and security.

After checking the distance and the perpendicularity with a square, I clamped the existing fence in place with two C clamps, one at each end.

Building the table saw fence

The diagram above shows how the four MDF strips are connected to form the fence. These were glued together, nailed with brads, and screwed for extra strength.

To ensure that the screw heads would not protrude from the fence’s surface, the pieces were drilled (clearance holes only) and countersunk before assembly.

Once glued and nailed. The pilot holes for the screws could then be drilled, and the screws could be driven home.

I chose to make both sides of the fence equal so that it could be used either right-handed or left-handed, although I do most of my cutting with the fence to the left or right of the blade.

I could have also done the same thing, using a 2″ x 4″ aluminum C channel rather than the two middle strips of MDF. However, this would have required buying one more type of aluminum extrusion, adding more money to the project cost.

I also made the table saw fence overly long, just as I made the rail excessively wide. My table saw has a support extension behind the front table saw itself, so I made the table saw fence just long enough to reach this support, even at its most extended extension.

This increases the surface I have available aftermarket table saw for the workpiece to ride against, helping to ensure that I run it through the table saw straight and evenly.

The aluminum angle, shown in the drawing above, forms the “T” head of the fence and is bolted to the bottom of the fence. I would recommend using three to four bolts, for maximum accuracy, precision, and security, along with nylon insert locknuts.

After all, this is the most specific and critical part of the assembly, as it must be perpendicular to the fence.

To more accurately check perpendicularity, use the fence, with the T head attached, as a square to mark a line on a piece of sheetrock or plywood.

Then flip the fence around, putting it on the other way. If it is exactly square, when you mark and measure the line from the other side, it should exactly overlap your measured original line.

Making the Locking Mechanism for Table Saw Fence

I use a knob and screw as a lock rather than an over-the-center lever mechanism to keep weight and make the fence easier to build.

Not only are those harder to build, but they must also be exact to work correctly. A screw and knob, on the other hand, is something easily accomplished in a home workshop.

Before we look at the locking mechanism, we need to talk about the “T” head for the fence. Opinions differ, but most good fences have a head that is about 1/3 the length of the fence. I would modify this by saying your head should be at least eight inches long.

However, no longer than a foot will be difficult to work with unless you have a large saw table. Be sure to radius or chamfer the corners of the aluminum angle you use for the “T” so that you don’t injure yourself when you run into it.

The locking bar, which goes inside the fence rail, should be roughly an inch the same length as the fence “T.” You can make it out of virtually whatever material you have available. Still, it should be at least an inch and ¼” thick and able to support being threaded without the threads pulling out. This pretty much limits us to aluminum or steel.

Table saw locking mechanism

As you can see in the diagram above, the locking mechanism consists of nothing more than a bolt with a knob attached, running through the T head and into the fence rail. On the inside, the bolt goes through the locking bar. To lock the fence in place, all that is needed is to tighten the knob once the fence is positioned.

You must use a good knob or knob/screw combination that won’t collapse as torque is applied. I would also go for the most significant thread size you can reasonably fit through the opening in your frame rail.

If you can get it, use fine threads, which will be easier to work with. You can buy these through industrial supply companies rather than trying to buy one at your local hardware store or home improvement center.

You will need to drill and tap the locking bar to accurately measure and match the thread of your knob/screw. If necessary, cut the knob/screw to length, and grind a chamfer at the end of the bolt.

You want it to go all the way through the stock locking bar, but you don’t want it to be able to hit the bolts that are holding the fence rail to the table saw table.

One last item that is needed is a spacer for the knob head to press up against when it is tightened. This must be made of some metal, as the tightening of the knob will try to compress it.

Plastic, for example, will crush, and your fence won’t be secure. Placing a washer between the knob head and this spacer to act as a thrust washer will help it to tighten and loosen a bit smoother.