Wood has always been prized for its natural charm and durability. But when used outdoors, not all wood holds up the same. Some species begin to decay after just a few wet seasons, while others can survive for decades in the elements. The secret? Rot resistance. This guide explains why some woods naturally resist decay, which species to choose, and how to work with them for long-lasting results.

Why Wood Rots (and What You Can Do About It)

Rot sets in when fungi feed on the structural components of wood, especially in moist environments. One of the main offenders is Serpula lacrymans, known as the dry rot fungus, though it ironically thrives in damp wood. Once wood reaches about 20% moisture content, it becomes highly vulnerable.

In nature, this decay returns dead wood to the earth, enriching the soil. But on a deck or raised bed? Not so great. The good news is that certain woods contain natural chemicals that defend against fungal invasion, giving them built-in longevity.

Moisture management is everything. Water doesn’t need to pour in—it just needs to linger. Shade, poor ventilation, or failing to seal end grains can trap moisture long enough for rot to start. Always allow for airflow and drainage, and avoid embedding wood directly in soil unless it’s rated for ground contact.

Interior materials like MDF swell and break down when exposed to humidity. Even treated wood isn’t foolproof if you leave the cut ends exposed. To prevent early failure, seal all cuts and joints with exterior-grade products.

What Makes Some Wood Naturally Rot-Resistant?

The natural durability of wood depends largely on what’s happening inside it:

- Heartwood Density – Older heartwood has fewer nutrients fungi want.

- Protective Oils – Species like teak and cedar produce oils that repel moisture.

- Antimicrobial Extractives – Some woods contain natural chemicals that ward off fungi and pests.

Western red cedar and Alaskan yellow cedar, for example, produce thujaplicins—natural fungicides that prolong outdoor lifespan. Black locust is loaded with flavonoids that actively repel decay.

Trees that grow in wet climates, like tropical hardwoods, have adapted to constant moisture. That’s why ipe and teak hold up so well outdoors—they evolved to. Even when more expensive, they last so much longer that they can save money over time.

Some species, like redwood and Spanish cedar, also give off a scent that deters insects, adding another layer of protection in pest-prone areas. These aren’t just cosmetic details—they help preserve structural integrity.

Porosity matters too. Open-pore woods soak up water quickly. Closed-grain woods like mahogany, walnut, and ipe do better in damp environments. How the wood is milled, dried, and stored also affects its future resilience. Always choose seasoned wood and allow for proper acclimatization before installation.

Budget-Friendly Rot-Resistant Woods

If you’re on a budget, these species still offer a solid defense against decay:

- Cypress (Janka: 510 lbf) – Lightweight, workable, and holds up well outdoors.

- Redwood (Janka: 480 lbf) – Weathers beautifully and is naturally insect resistant.

- Old-Growth Pine – Denser and richer in resin than modern pine, harder to find.

- Cedar (Janka: 350 lbf) – Classic for garden use, fencing, and lightweight furniture.

- White Oak (Janka: 1,360 lbf) – Strong and water-repellent, commonly used in boatbuilding.

🛠️ Product Tip: Cedar Boards – Rough Cut for Raised Beds (Amazon)

Cedar and redwood are soft enough to work easily with hand tools but are still naturally decay-resistant. Just be sure to buy true heartwood—the sapwood isn’t as durable. Many DIYers also appreciate how softwoods take stain and paint evenly.

Bonus: Cedar and cypress are aromatic, naturally deterring bugs and adding a fresh scent to your workspace. These woods are ideal for beginners and weekend builders working on planters, lattice screens, or outdoor trim.

Premium Woods for Maximum Longevity

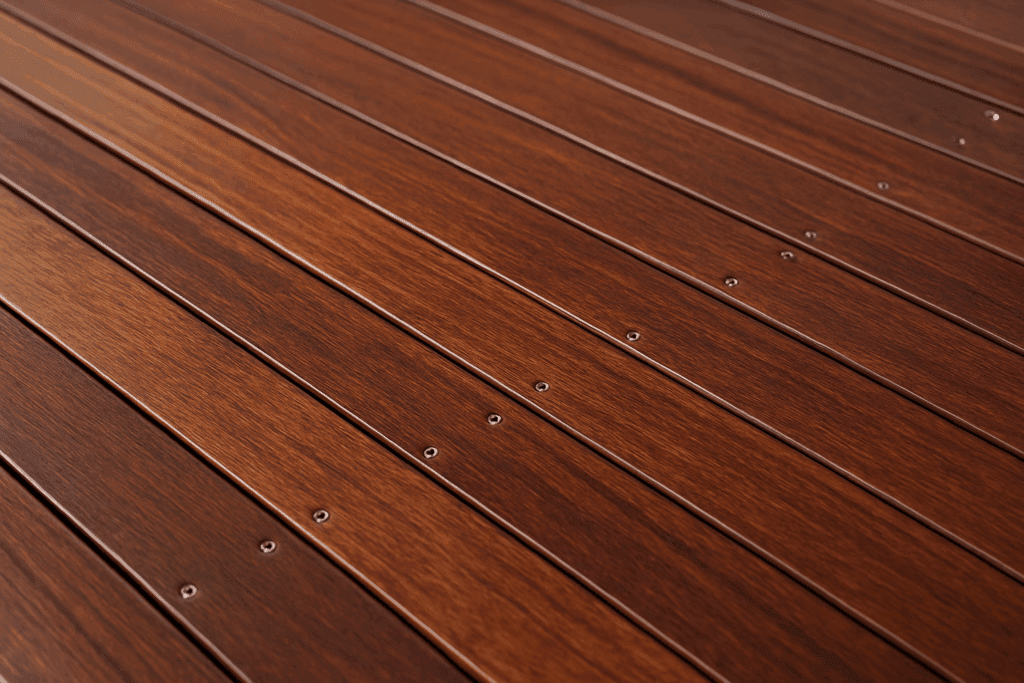

Choosing premium rot-resistant wood isn’t just about longevity—it’s about investing in the aesthetic and structural integrity of your project for decades. These high-performing woods are often used in architectural applications, boardwalks, and heirloom outdoor furniture because of their strength, density, and natural beauty. Their chemical makeup gives them a natural shield against decay and insects, but their visual qualities—tight grain patterns, rich coloration, and smooth finishes—make them desirable far beyond performance. These woods not only endure; they elevate your project’s appearance and value.

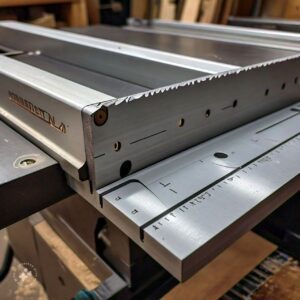

What’s important to keep in mind is that many of these hardwoods are significantly denser than your average pine or cedar, which can pose challenges in terms of machining and fastening. Teak and ipe, for instance, will quickly dull your tools, and pre-drilling holes is a must. But the tradeoff is reduced maintenance over time. These woods resist splitting, warping, and cracking, even in harsh climates where moisture and temperature swings destroy lesser materials. When properly sealed, they can withstand freeze-thaw cycles, high humidity, and UV exposure with minimal fading or degradation.

Moreover, these species often boast impressive sustainability records. Black locust, for example, is native to North America and grows quickly in managed forests, making it a renewable choice with excellent durability. Accoya, though engineered, uses fast-growing pine and undergoes a non-toxic treatment that makes it dimensionally stable without compromising environmental impact. Many suppliers now offer FSC-certified versions of these woods, allowing builders and homeowners to make ethical choices without sacrificing performance.

How to Select

When selecting among premium options, think about the total lifespan of the structure and how much time you want to spend maintaining it. If you’re building a bench for a shaded, damp corner of your garden, black locust might be your best bet. For a sun-soaked beachfront deck, ipe or teak will last longer than almost anything else. And if your project is both decorative and functional—like a custom outdoor cabinet—mahogany offers the perfect balance of workability and elegance.

If you’re building for the next generation, these premium woods offer unmatched endurance:

- Teak (Janka: 1,155 lbf) – Dense, oily, and time-tested in boatbuilding.

- Ipe (Brazilian Walnut) (Janka: 2,350 lbf) – Rock-hard and virtually impervious.

- Black Locust (Janka: 1,700 lbf) – Incredibly strong, American-grown, and rot-resistant.

- Accoya (Janka: 922 lbf) – Treated pine that’s stable and long-lasting.

- Mahogany (Janka: 800–900 lbf) – Beautiful, workable, and moderately durable.

- Spanish Cedar (Janka: 600 lbf) – Aromatic and insect-repelling.

- Mesquite (Janka: 2,400–2,600 lbf) – Dense and ultra-durable.

- Black Walnut (Janka: 1,010 lbf) – Decorative and reasonably durable when sealed.

Ipe and teak have earned reputations for long-term resilience. Ipe, in particular, can last over 40 years with little maintenance. While harder to saw and drill, these dense woods are ideal for high-traffic areas like decks and stairs.

Accoya, a modified pine treated through acetylation, resists warping and swelling and is often used in extreme climates. It’s especially good for doors and windows, where dimensional stability matters most.

Mesquite and black locust are so durable that they’ve been used in railroad ties, bridges, and even outdoor sculpture. They’re hard on tools but nearly immune to decay. Builders who value performance above all else find these species well worth the effort.